- The Timeless Cost of Learning to Kill (Reading Now)

- The Timeless Cost of Learning to Kill, Part II

Part 1: Of Bonnets and Bullets

Allan Young, Canadian psychologist and Professor at McGill University, tells us that Post Traumatic Stress Disorder is an invention of the latter half of the 20th century. PTS is considered primarily an American invention developed after the Vietnam War to help diagnose and treat veterans of that horrific conflict.

Young is far from alone in this belief that PTS is not “a timeless or universal phenomenon newly discovered,” but

a “harmony of illusions,” a cultural product gradually put together by the practices, technologies, and narratives with which it is diagnosed, studied, and treated and by the various interests, institutions, and moral arguments mobilizing these efforts (Young).1

This article is the first in a series examining this thesis put forth by Young and others. We will first present their perspective, then critique it using the works of Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, author of On Killing, and Bryan Doerries, author of The Theater of War to demonstrate that PTSD – or whatever this thing is – is as old as anything in written history.

First, my Biases and Bonafides

I’m a former Marine I’m too close to the subject of study to back away and find some easy measure of impartiality; I’ve had, and in some ways have still got, too much skin in the game. I’ve seen counselors for my own PTS and have made great strides toward modest goals; when I meet other veterans my substantive concern is to help them if they want and need it, or refer them to the help they need if I am unequipped to offer it.

I believe the “cultural product” that is PTS, if that is what it is, provides a framework for discussion that is indispensable. I would liken it to finding one’s self in a mine field – which my dumb ass has done – and being able to wend your way back reverse-wise in your own boot-prints. Being able to deconstruct the path taken, the decisions made and tacit agreements reached with your past, allows a man to back his way out to safety, and some measure of sanity, again.

Young’s description of PTS as a cultural product belies the veracity of my personal experiences. I would say there’s something actually there, something not entirely illusory. I will not upend Western thinking and insist both Young and I are right in the same time and in the same respect – if there is a true contradiction, one of us must be wrong, and certainly (probably) me.

As a blue-collar worker I don’t have the luxury of Young’s decades in the field of psychology, nor the perspective it offers. I move about my life, as Derek Summerfield might say, almost entirely unaware of my tacit agreement with the “collectively held beliefs about particular negative experiences” in our culture and as such am largely unaware that by conforming to “prevailing expectations and categories,” I am almost certainly committing myself to some small measure of “self-fulfilling prophecy” (Summerfield).2 Succinctly, if I’m taught by society to see certain events and situations as traumatic, they are, and if I believe I am wounded severely or permanently by them, I am.

Or, in the words of one old firefighter, my head may be so far up my own ass I can’t find it – my ass, that is – using both hands and a map. I don’t know if this is what Plato meant by his allegory of the cave, but it suffices as an admission that perhaps I cannot be other than a prisoner of my own essential beliefs. Sure is dark in here.

But I can’t shake the feeling that Young and Summerfield are referring to something different than I am when we both say PTS. Perhaps they mean PTS in toto as a psychological category and I can hear them whispering Beware the Veteran Industrial Complex which drives so much of the mental health industry. Billions of dollars evaporate yearly in the bowels of that modern edifice to inefficiency and waste, the Veteran’s Administration of the United States. The National Health Service in Great Britain, which takes all British citizens in its charge, is enduring it’s own death-waltz with the ever-expanding PTS industry. The moral wind, and the dollars, are flowing into all things PTS in a society that prizes grievance and victimhood over “survivorhood.”2 Now that is a self-perpetuating cycle.

When I say PTS I mean all of the cold-sweat inducing garbage whose proximate cause was my deployment to Iraq – the sleeplessness, anger at I-know-not-what, recurring nightmares, strained and broken relationships, the temptation to drink heavily and often – all of it. It’s far from anything I would call harmonious; the word usually has positive associations. If it is an illusion it is one on par with the rest of veridical experience and indistinguishable from the rest of reality.

When I say PTS I mean all of the cold-sweat inducing garbage whose proximate cause was my deployment to Iraq – the sleeplessness, anger at I-know-not-what, recurring nightmares, strained and broken relationships, the temptation to drink heavily and often – all of it. It’s far from anything I would call harmonious; the word usually has positive associations. If it is an illusion it is one on par with the rest of veridical experience and indistinguishable from the rest of reality.

The Dissonant Illusion

Could it all be a harmonious illusion, though? Would thousands of veterans not struggle with the symptoms we know collectively as PTS if no one had taught us to classify our experiences in a specific way?

A central assumption behind psychiatric diagnoses is that a disease has an objective existence in the world, whether discovered or not, and exists independently of the gaze of psychiatrists or anyone else. In other words, neolithic people had post-traumatic stress disorder as have people in all epochs since. However, the story of post-traumatic stress disorder is a telling example of the role of society and politics in the process of invention rather than discovery.2

I understand those words like I would if someone insisted the natural color of the sky is green. He’s writing in a language I understand but the conclusion is so far from my personal experience it’s like we’re saying two different things using the same term, PTS. Perhaps both of us are right after all – we’re talking past one another. Young and Summerfield, and many doctors like them, are talking excitedly about a neat pile of lacy bonnets over there, all classified and orderly. Lots of men like me are saying no, no, we mean this pile of bullets, yes, that one that stinks of cordite and sweat, around which the air is blue – right here.

The Argument for Invention

Derek Summerfield is an honorary senior lecturer for the Department of Psychiatry at St. George’s Medical School in London, England. He regards PTSD as “an entity constructed as much from sociopolitical ideas as from psychiatric ones.”2 As a “legacy of the American war in Vietnam” and the “post-war fortunes of the men who served there,” PTSD could be substituted for multiple other diagnoses like generalized “anxiety state, depression, substance misuse, personality disorder, or schizophrenia.”2 Men who would have been diagnosed with “battle fatigue” or “war neurosis” now had a “new diagnosis.”2

It is understandable that a pendulum that had swung so wide as to allow “baby-killer” and “psychopath” to be hurled at all men in uniform – whether they were volunteers, draftees, or had even been deployed overseas – would hasten back in the opposite direction.

Early proponents of the diagnosis… were part of the antiwar movement… they were angry that military psychiatry was being used to serve the interests of the military rather than those of the soldier-patients… [PTSD shifted] the focus of attention from the details of a soldier’s background and psyche to the fundamentally traumatogenic nature of war.2

Of Necessity and Invention

What made Vietnam so vile – or more vile than previous wars – to cause such a deluge of young men to return home broken? The necessity that preceded the invention of PTSD as an entirely new psychiatric category is precisely defined by Lt. Col. Dave Grossman in his book, On Killing. He quotes D. Andrade in the following:

Vietnam was an American nightmare that hasn’t ended for veterans of the war. In the rush to forget the debacle that became our longest war, America found it necessary to conjure up a scapegoat and transferred the heavy burden of blame onto the shoulders of the Vietnam veteran. It’s been a crushing weight for them to carry. Rejected by the nation that sent them off to war, the veterans have been plagued by guilt and resentment which has created an identity crisis unknown to veterans of previous wars (Grossman, 285).3

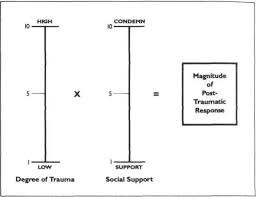

Grossman argues that there is a multiplicative relationship between the degree of trauma received in a given time span and the amount of social support offered to veterans by society at large. Even a rear-echelon post with little exposure to trauma can result in a high score when faced with maximized scorn from one’s contemporaries. The impact is even greater for a veteran who saw consistent combat and acted on his training to kill without hesitation.

For instance, a rear-echelon Motor Transport driver comes out of the war with a relatively low trauma score, we’ll say 3/10: he was on the receiving end of indirect fire at unpredictable intervals, sleepless nights for months on end, and more than once was involved in processing the bodies of his comrades-in-arms on their way home to their families but never had to kill anyone in direct conflict. If he returns in the height of anti-war, anti-veteran sentiment in the early 70’s, his score on the social support matrix may be high scorn, we’ll say an 8/10. The “magnitude of post-traumatic response” for this man would be relatively high despite the fact that, arguably, he hadn’t endured anything out of the ordinary for soldiers in war time (286).3

Remember, this is a multiplicative relationship between “the degree of trauma” and the kind of “social support” this veteran receives (286).3 In the example above, old Motor Joe has a raw score of 24 out of a possible 100. Not too bad. Could be a lot worse, right?

This number is intended to enhance our concept of what it’s like to face the traumatogenic experiences of war and return home to a contemporary society which exhibits varying degrees of support or contempt; it isn’t printed and handed out on Joe’s VA card. It indicates that, while his experiences were sub-par on the trauma scale, Joe still has no one to talk to about his experiences, no one wants to hire him, he’s afraid to admit he’s a veteran even in traditionally sympathetic circles, and girls sure as shit aren’t going to date him. I’m looking at you, Hanoi Jane.

Imagine what this kind of relationship indicates for a high trauma score returning to a society demonstrating the utmost contempt. Vietnam was unique in this aspect: in all previous conflicts our boys returned home to a welcome reception.

In the late sixties and early seventies, these men came home to a vile segment of society that rejected and spat on them, making their roads to recovery – their return to normal life – nigh-on impossible.

Today, the PTS Industry Rules the Earth

[The diagnosis of] post-traumatic stress disorder legitimized [the veterans’] “victimhood,” gave them moral exculpation, and guaranteed them a disability pension because the diagnosis could be attested to by a doctor; this was a potent combination (Summerfield).2

Summerfield recognized the growing trend in British society toward the popularization of PTS: by “September 1999” there were “more than 16,000 publications” indexing the diagnosis of PTSD:

Originally framed as applying only to extreme experiences that people would not expect to encounter every day, it has come to be associated with a growing list of relatively commonplace events… increasingly the workplace in Britain is being portrayed as traumatogenic even for those who are just doing their jobs: paramedics attending road accidents, police constables on duty during disasters, and even employees caught up in what would once been described as a straightforward dispute with management.2

The Declining Social Utility of being a Survivor

Its been 18 years since Summerfield wrote his article. It reads like he’s evaluating current events:

Today there is often more social utility attached to expressions of victimhood than to “survivorhood” … to show that you have been wronged you seek to show that you were not just hurt but impaired… there is a veritable trauma industry comprising experts, lawyers, claimants, and other interested parties… a kind of social movement trading on the authority of medical pronouncements.2

The definition of PTSD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders has changed accordingly, payments are being awarded for ever-widening tolerances – the beasts, and by this I mean humans as a collective herd – are adapting to the cash flow. The relative financial ease of being disabled (and having someone else pay you forever) is a material, in-your-face benefit; it’s cash in-hand for those willing to pursue it. The virtues of self-reliance, stoicism in the face of adversity, and the composure necessary to endure the every day hardships of life, and its occasional tragedies, require work. Virtue has the added detraction of being an abstract reward and is notoriously difficult to quantify.

The definition of what qualifies as a “traumatic stressor” has widened considerably:

…accidents, muggings, a difficult labor (with a healthy baby), verbal sexual harassment, or the shock of receiving (inaccurate) bad news from a doctor even in cases in which the incorrect diagnosis has been rescinded shortly afterwards.2

By DSM-IV the definition was wider still, including “the experience of hearing the news that something bad has happened to someone to whom one is close: second hand shocks now count.”2

The Dubious Classification of Stress as a Disorder

The fashioning of smart weapons out of snowflakes is perhaps the greatest feat of magic performed by U.S. Marine Corps Drill Instructors. They use continual stress and sleepless nights and hammer on the basics of training until they’ve got a young man or woman they can actually make use of – that is, one willing to instantly follow orders, period.

The Corps isn’t for everyone. There are civilians who can’t make the cut, and a few in my boot camp platoon that seemed to just come apart under the stress. One started cutting himself, another threatened the DI’s during our weeks at the rifle range, and another just tried to escape to the highway that was tantalizingly close.

Stepping off the bus at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego was like landing in another world. Accustoming us to the stress of military life and the prospect of potential future combat is the DI’s job. The old adage that to boil a frog you heat the water one degree at a time applies here – it makes them used to the heat. If you immediately throw them into boiling water they’ll jump right out. The metaphorical water is hot in boot camp and hotter than some young men can take. Having your mind and body beaten into the shape of something else is entirely unpleasant but it didn’t rise higher than the most stressful period of my life, up to that point.

Do the three washed out recruits I previously mentioned fashion their memories into traumatic events that haunt them, to one degree or another, forever? What baseline did they come to boot camp with? What was an acceptable amount of stress they were willing to tolerate within the bounds of what they considered “normal”? What had their families and social circles prepared them to accept as such?

…human pain is a slippery thing, if it is a thing at all: how it is registered and measured depends on philosophical and socio-moral considerations that evolve over time and cannot simply be reduced to a technical matter… [which] can be understood in standardized ways and are amenable to technical interventions by experts.2

Which is Heavier: the Pile of Bonnets or the Pile of Bullets?

I prefer to drop the disorder off the end of PTS because it doesn’t help me think of the issue as one I can surmount. I don’t have a disorder, but a giant wad of interrelated memories, most of them benign by themselves, some few entirely horrid, that work together in to influence my behavior in sometimes unpredictable ways.

What Young and Summerfield say about PTSD is right in the sense that, if doctors have “the power to award disease status and the social advantages attached to [it],” there needs to be a thorough re-examination of

What Young and Summerfield say about PTSD is right in the sense that, if doctors have “the power to award disease status and the social advantages attached to [it],” there needs to be a thorough re-examination of

…our definition of the disorder as a disease and decide whether it has sufficient robustness and explanatory power to apply to the diverse uses to which it is now being put.2

PTSD as a diagnosis has lost its potency by virtue of its multiplication and dilution. Consider that the term “hero” used to mean something until every glad-handing politician started throwing it around at everyone in uniform and you’ll catch my meaning. Young and Summerfield must save the mental health industry, and by some measure society at large, from the implosive powers of unrestrained victimhood. We can’t blame them for that; they are mental health professionals with character and as men they must draw an arbitrary line and defend it somewhere.

What I take issue with is their apparent willingness to toss Joe out with his wash water, or better yet lump him together with the neckbeard who can’t go anywhere without his waifu pillow.

Conclusion

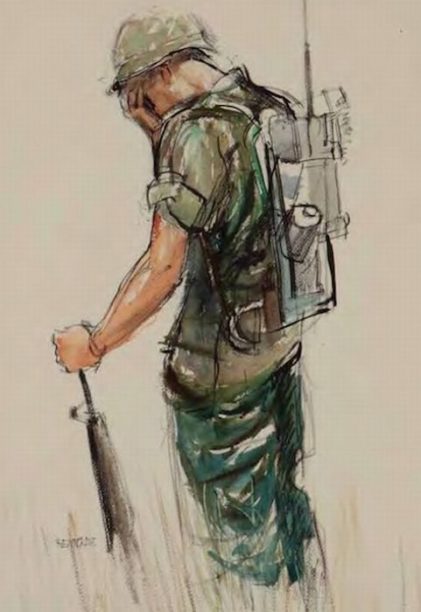

Whatever we decide to call PTS, there is still something there. You can see it manifest in the lives of a great many veterans, men and women who have been partially inoculated against trauma but nevertheless find themselves struggling against an enemy that is elusive and difficult to define. You can see it in the pages of history, if you’re looking for it – an no, I don’t mean if you anachronistically project your assumptions on old texts. I mean pay attention to writings like the Sophoclean play Ajax; it is perhaps the best surviving example of the destructive power of PTS in history.

Re-reading the Old Testament, with its mass-slaughter and total wars, is also revelatory. The way the Israelites handled their veterans in the days following a battle is an effective and proven strategy for minimizing the effects of PTS on a warrior population. We will see how it was unwittingly repeated for American veterans of both World Wars and how different those two generations were from their Vietnam counterparts.

With the help of Lt. Col. David Grossman and Bryan Doerries, that’s where we’ll go next. Stay tuned.

Trending

References:

- Young, Allen. "The Harmony of Illusions: Inventing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder." Publisher's Abstract. Princeton University Press, December 1995.

- Summerfield, Derek. "The invention of post-traumatic stress disorder and the social usefulness of a psychiatric category." British Medical Journal, vol. 322, January 2001.

- Grossman, David. On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society. Little, Brown and Company, October 1995.